December 21st, 1862

Fairfax Station, Dec 21st

Dear Wife,

Today, which is Sunday, I take an opportunity to write you a letter. I wrote a little yesterday and sent it for I did not know then I should have a chance to write again so soon for everything is so uncertain that we don’t know five minutes beforehand what the next move will be. We are just as likely to start tomorrow for Harpers Ferry as any way.1 We left there for Dumfries to be in supporting distance of Burnside, but after his defeat2 (I can call it nothing else) we turned back and came to this place (which is about 30 miles south from Washington) and encamped in a fine woods.

You may think that we can live pretty well near a railroad station, but there is nothing here that we can get but salt meat3 and “hard tack”4 and we have had only half rations of that ‘till today. I have not really suffered from hunger but I could have eaten more but today we have drawn full rations of the above named articles. On the march, we eat raw salt pork and hard tack and nothing else, but that tasted good. We had sugar and coffee which we made in our tin cups. You should see us cook, we put a piece of pork on the end of a stick and hold it up to the fire and put our hard bread on another and hold it under the pork which serves the double purpose of toasting the bread and saving the grease.

We were eight days on the march, we passed through as fine a farming country as one could wish to see the first four days, but the last two before we turned back the land was low and swampy, covered with small pines. I should not like [to] live here, but if the country was settled I should like a farm in Loudon Valley, but it looks desolate even there (as it would in the Garden of Eden if the dogs of war should pass that way). You have little idea of war where you are even if you should lose your best friend and protector, it is impossible to prevent soldiers from marauding hogs, sheep, chicken fences, and even buildings are taken by them to make themselves more comfortable and I can scarcely blame them, they need all they can get to make them comfortable. Wherever I have been in Virginia, it seems as though the “abomination of desolation had been set up”.

Fields, houses, and barns are in ruins, fences and buildings burned, and the cattle butchered, but the work of destruction has only begun for God has a terrible punishment for this nation to punish it for the horrible sin of slavery. Nations cannot be punished in another world like individuals for they have no future existence so they must necessarily be punished here and I can but believe when this nation is purged of it’s darkest sin it will be restored to it’s former glory but no one can tell what calamities are in store for us before that time.

I think I have said enough about the war and myself. I will now write about you and things in general. I have had 3 letters from you since we stopped here and they have been a great comfort to me for every word from your pen is like the smell of spices in the king’s garden and I look for another as soon as I get one with as much impatience as though I had not had one in six weeks, but thanks to your kindness I don’t often look in vain when a mail comes to the Regt. You seem to think you write poor letters, but I can assure you that your composition is superior to any I have seen and I have had the privilege of reading many letters that have been sent here and I have taken the liberty to show the Capt. some of yours.

I am much interested in all you say about our little darling. I wish I could say something to her but she could not understand me. I need not tell you to guard her carefully for I know you are too much inclined that way. I am glad you take her outdoors every day. My experience teaches that outdoor exercise is good for the health.

I was very sorry to hear that your health was not good. If any of you should be sick, I want you to write me just how you are. It is the very thing that makes letters valued that we may know how things are at home. When I write to you I tell things just as they are, if I am sick I say so and I want you to do the same. It may be so that I come home if you should be very sick, I would get home if possible.

The Capt. was just here, he says that he has heard that this brigade is to go to Martinsburough or Harpers Ferry. If so, perhaps I shall not have an opportunity to send you another letter ‘till we get there.5

It don’t seem likely that this Regt. is to do any fighting but we have to go through more hardships than any in the service and as a consequence there is a good many that have given out. One man died out of our Co. last week, he was from Waterbury6. There are several sick but most of those from Hamden are getting better. Brain and Mark have come on here, they say that the boys are getting better. Beckwith and Cook are sick here. Cook has a bad cold and the Dr. is afraid of lung fever while Beckwith has the inflammatory rheumatism. I take the best care of them I can, I have got them into the hospital tent, put up a stove, and detailed a man to take care of them. They seem to be comfortable. I will do all I can for them.

I must close this soon and go and draw the rations from the commissary. I had intended to say something of the effect of camp life on the mind but have not time and space. You must write me all you can think of about everything. Give my love to mother and all my friends.

Yours with much love and many kisses,

C. B.

-

The Twentieth will stay in this camp until January 17th, 1863. ↩

-

This is speaking of Burnside’s tragic defeat at Fredericksburg. ↩

-

Salt pork was one of the more common varieties of meat issued. It was pieces of pork that had been essentially pickled in salt. It was so salty that it could be eaten relatively safely raw, but often required being repeatedly boiled in fresh water to pull out some of the salt and make it palatable. Each soldier would be issued ¾ lb. a day while on the march. ↩

-

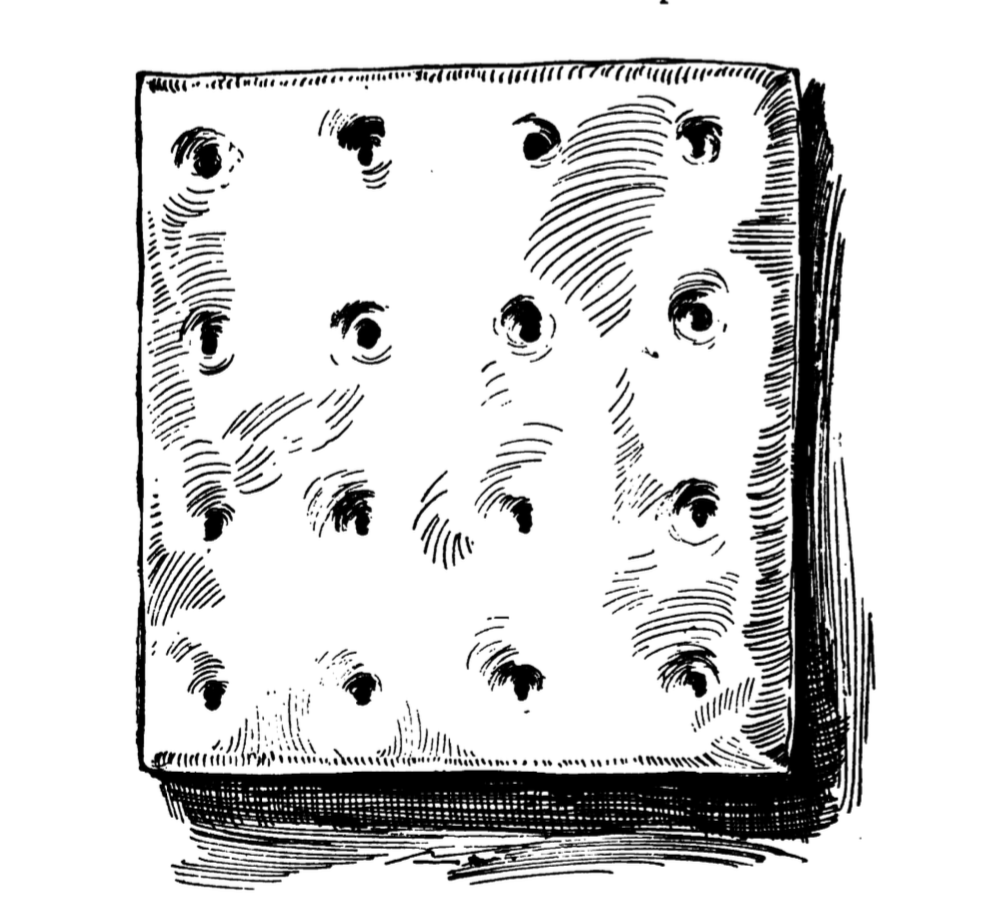

Besides the meat, army bread (more commonly known as “hardtack”) made up the bulk of the marching ration that US soldiers received. These crackers were made of flour and water, and then had the water baked out. Occasionally, a small amount of salt would be added to the mixture. The end result was a 3” × 3” × 0.5” cracker that could not be called tasty. Each soldier would be given about 10 per day.

A sketch of a “hardtack” These crackers were issued in three distinct flavors: too hard to eat, too moldy to eat, and too infested with weevils to eat. The soldiers would eat any but the moldy variety. The hard type was usually boiled in coffee or crumbled then fried. Regarding the weevily kind, the soldiers found that they would float to the top of a cup of coffee, which made them easy to skim off. ↩

-

This rumor was not validated, the 20th would stay in Fairfax Station for the near future. ↩

-

This would have been Pvt. Henry Farrell. ↩