December 20th, 1862

Fairfax Station, Dec. 20th

Dear Wife,

We arrived here last Thursday about as destitute as a soldier need be for you can guess (if all we have is what we can carry on our backs) that we should not have much left after eight days marching1 in mud up to our knees. When we started I had two woolen blankets but after carrying them two days I was obliged to give away one in order to lighten my load but I am happy to be able to write you that I am well after what we have been through. We have lain on the ground every night since we left Loudon Valley, but I have slept comfortable every night but two, one night it rained and I waked up and found myself in a mud hole and felt quite uncomfortable, and last night I slept cold, but I mean to sleep warm tomorrow.

I got two letters from you last night, it was the first mail we have had in twelve days. You can guess whether they were acceptable or not. I dare not tell you how we have lived or what we have endured for fear you will think we have suffered more than we have, but when I tell you that raw salt pork2 and “hard tack” (army bread)3 tasted better to me than apple pie ever did at home, you will think I have been hungry as well as tired. We passed through a beautiful country and had many interesting incidents that I might write you but it is so cold today I can’t write and I don’t know when we shall be better situated.

You must try and be contented with short and poor letters ‘till I can find a comfortable place to write. I am getting discouraged myself about the war, there is so many mistakes made it seems as though we never was to see the end of it, but we must do our duty and give the result to God.

I was glad to hear that Mr. Beach4 had arrived safe at home, but I was sorry that you should think him hard because nature gave him a horrid looking face. I always thought him the hardest looking customer I ever saw, but since he has been with us he has been very sober and gentlemanly in his conduct.

The watch has seen hard times, the crystal got broken and I was obliged [to] carry it in my pocket for we have no place to keep such things safe unless we keep them with us. Austin traded and got a double cased watch, he said I might have it for what it cost him (three dollars). I kept it awhile and found it a good watch and as it was necessary for me to have a timepiece I bought it and want you to get that [old watch] fixed and have it for your own use. I don’t think it will cost much.

I want you to write me often and tell me just how you are and all the rest of the folks. It made me feel blue to hear that you are not well, do take good care of yourself. I can’t write much today, I am too blue. We have heard of Burnsides repulse5 and it is a damper on us. I hope things will look brighter before long.6

Yours with much love and many kisses. Kiss my little darling for me and write me all about her. Give my love to all,

C. A. Burleigh

-

This march started from the Loudon Valley, proceeded towards Fredericksburg, cut short 5 miles from Dumfries, then headed back north to Fairfax Station. ↩

-

While on the march, soldiers would be issued 1 lb. of meat per day (they would typically be issues 3 days of rations at a time) in addition to ten hardtack crackers and maybe some dehydrated bricks of vegetables (“desiccated vegetables”, or “desecrated vegetables”, as the soldiers liked to call them). However, in this case, the 20th Connecticut was on half-rations and received no fruits or vegetables.

Salt pork was one of the more common varieties of meat issued. It was pieces of pork that had been essentially pickled in salt. It was so salty that it could be eaten relatively safely raw, but often required being repeatedly boiled in fresh water to pull out some of the salt and make it palatable. ↩

-

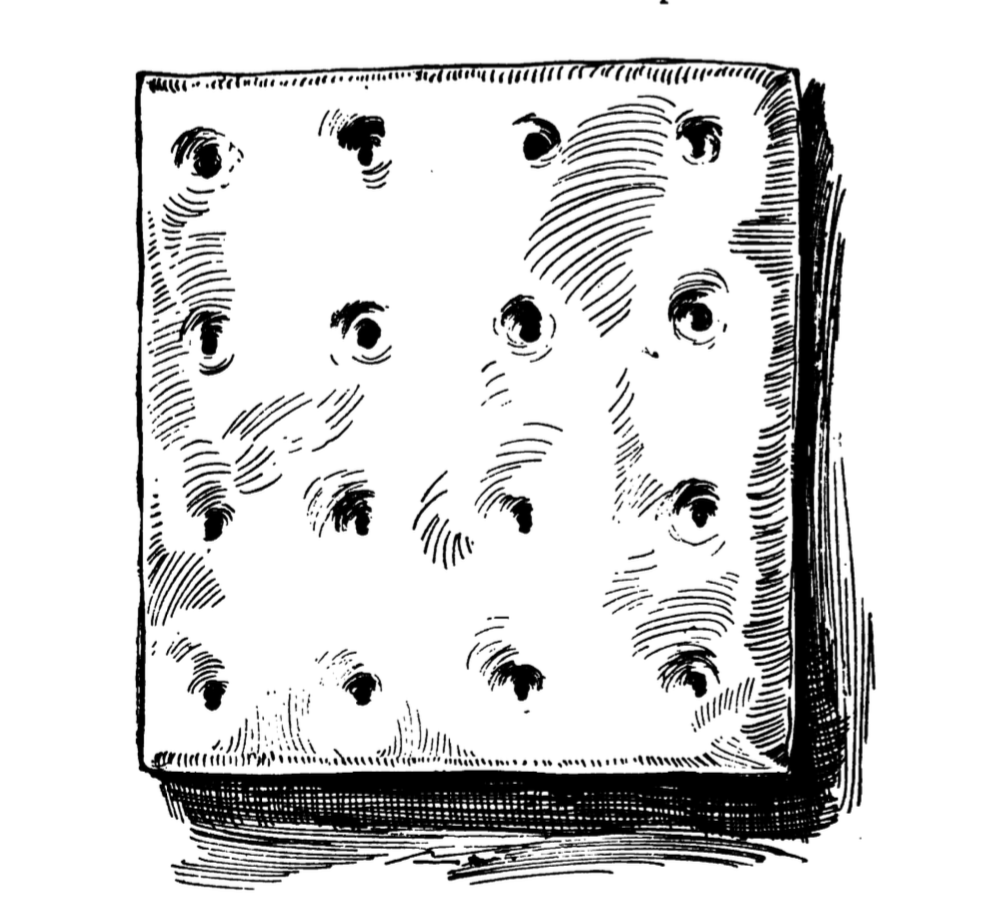

Besides the meat, army bread (more commonly known as “hardtack”) made up the bulk of the marching ration that US soldiers received. These crackers were made of flour and water, and then had the water baked out. Occasionally, a small amount of salt would be added to the mixture. The end result was a 3” × 3” × 0.5” cracker that could not be called tasty.

A sketch of a “hardtack” These crackers were issued in three distinct flavors: too hard to eat, too moldy to eat, and too infested in weevils to eat. The soldiers would eat any but the moldy variety. The hard type was usually boiled in coffee or crumbled then fried. Regarding the weevily kind, the soldiers found that they would float to the top of a cup of coffee, which made them easily to skim off. ↩

-

William Beach was a corporal in Company I until he was discharged for disability on December 10th, 1862. ↩

-

Five days prior to this letter being authored, General Burnside, at the head of the Army of the Potomac, suffered a staggering defeat at Fredericksburg. This was one of the darkest points of the war for the North — on the battlefield, they had lost every battle they engaged in. ↩

-

The regimental history of the Twentieth had this to say of this period of time:

“Half starved as they were, enfeebled by exposure to the wintry elements, and with no money in hand to send home to their families, it is not to be wondered at that the men of the Twentieth and their comrades could, from the bottom of their hearts, have declared, “Now is the winter of our discontent.” But they had another lesson still to learn, viz: that patient endurance, starvation and wrong, is simply a part of a soldier’s duty. He must suffer all things, and complain of nothing, except to the winds.”