September 21st, 1862

Camp Chase, Sunday Sept 21st

Dear Wife,

It is with pleasure that I again essay to speak to you through the medium of a letter. It is a comfort to me to have the privilege of writing to and more of a privilege to hear from you.

I received your letters last night, it was like meat to the hungry, or water to the thirsty! You have no idea with what eagerness the soldier receives a message or how sorry they look when disappointed. Some of the boys got letters on Friday. It fairly made me blue because I did not, but I know it was no fault of yours when I did not receive one. It made the tears come to my eyes to read your loving words and feel your sympathy.

You may expect to get a long letter this time, and if I have time to write it for there is enough passing around here that it is interesting enough to fill volumes, but I am so busy that I have little time to take notes, but I am foolish enough to suppose that what interests you most is what concerns me. I have been very well though I found myself pretty well used up after my march for Capital Hill to this place1, but am well now with the exception of a slight cold.

We were out on a Grand Review yesterday. There was about 15,000 of us drawn in an open field. The lines extended as far as the eye could reach, it was a grand sight, I can tell you, but I suppose you would have called it a sad sight to see so many men that are so soon to be lead to battle where so many must be killed, but perhaps the war will be over before we ever see a fight. They say that McClellan is giving the Rebs fits. I hope so though I have no objection to going into battle if it is necessary.

We are in camp in a poor locality, We have to go half a mile to get water to drink but I suppose it is as good a place as there is about here.

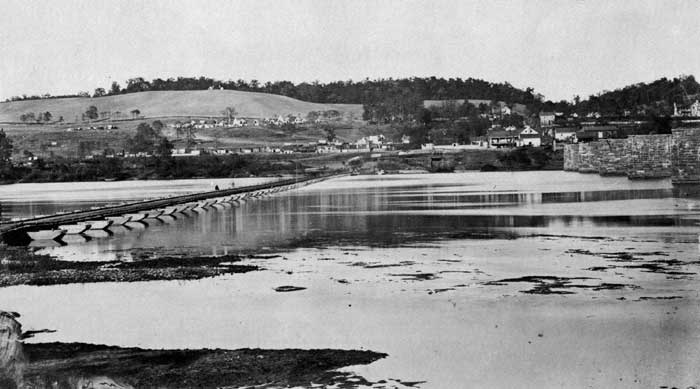

I have been down to the Potomac to survey. It is about 3 miles from here – a long walk – but I was bound to find a good place to wash up in. I gave a man 13 cents to wash my clothes. I am bound to keep clean if possible, Willis says that after we have been out 3 years we shall prefer to sleep in the mud with the hogs rather than sleep in a good clean bed, but I don’t think it will be so with me.

Will is a little blue, but I am as contented as possible away from you and my home, but I can tell you there is no place like home. Every inch of ground about the old house seems sacred to me (for your feet have pressed it all). I think of home as the place of peace and rest, an antitype of that home about where, I hope, we shall dwell in peace forever.

I am going to hear a sermon this afternoon for the first time since I left home.

The boys all behave well so far, [some] of the them much better then they did at home, but it is no place for improvement.

You wanted me to write to Henry about Fanny2, but I don’t see the necessity. If Boss Ed wants her, let him have her on his own terms, he will do better than he talks, besides I would rather give him a ton of hay than to let Henry have her. Besides, Henry don’t want her. We only spoke of taking her to accommodate [unintelligible] for the tax. I believe I paid that the night that Dennis was up to our house, but can’t tell for certain. Anyway, if it is not worth calling for it is not worth having. The more I think of it the more I thinks I paid it. You had best be pretty sure that I did not before you pay him again.

If there is any more business you want to know about, just write me and I will tell you all I know about it. I wrote you in my last that E. D. Dickerman was to hand you over fifty dollars, I hope he has done it before this, if he has not you had better ask him about it.

I must now take the boys up to the Chaplains tent and will finish the letter tonight.

Back from church, had a very good sermon for a Methodist, don’t know how much good it may do, hope it much.

I shall have to make short with this letter for we have got to go on dress parade in half and hour. I hope you will be able to read this better than you did the others – for you must have made a mistake for I said that the door slammed against my legs and not the sore, for I have no sore on me.3

Now, dear wife, you need not worry for me. I probably knew what I had got to come to before-hand and made every sacrifice cheerfully for the sake of my country, and I think she is worthy of it, for she has given me a home and protection to my family and I am not the man to turn my back on her in her hour of need. I hope to come back to you sound in body, mind, and above all in moral-principal, but if I am to die I hope to meet my fate like a man and a Christian.

“There is a tear for all who die, and mourners at the humblest grave, but nations swell the funeral cry, when death has triumphed over the grave.”4

You say that O’Brian has so much work to do that he can’t dig the potatoes. If so, he must get them dug, it will be time enough to dig those on the hill next week and those in Aunt Sarah’s lot the week after, but I don’t care how quick he digs those on the hill. I think that I will send him a line but you must not be afraid to call on him or anybody, else just trump up to them, that is the way to do it. I can not write any more tonight, though I have not said half of which I want to for I love to talk to you though at a great distance. Dear wife, you must write often while I am where I can get your letters. I will.

Goodnight, God bless you and kiss the baby often for your father and give my love to mother. All the boys are well except Isaac Warner5, he has a fever.

P.S. Dear wife, I shall have to slip in another bit of paper by way of P.S. to tell you that you need not send me an armor vest for I can buy enough of them for two dollars apiece6.

I was sorry to hear the baby had been sick, but was glad to hear that she was better. If the dear little thing should die I fear that I should be in as bad a condition as Mr. Pardee. I look at her and you everyday, that is your picture, they are such a comfort to me.

-

The march from Washington, D.C., to “Camp Chase”, was executed on the 17th of September – four days prior to the authorship of this letter. He describes this march a little bit more in his letter of the 18th:

We left Capital Hill yesterday morning and arrived at this place after a four hour march at 12 o’clock. We had no dinner or supper except what we bought. Some of the boys thought it mighty tough but I stood it like a horse, though I am a little lame this morning. ↩

-

“Fanny” is the horse that Cecil owns – and which Caroline is attempting to sell. Caroline describes her attempts to strike a deal in her letter on the 21st of September. ↩

-

In Caroline’s letter of the 17th, she mentioned:

…when speaking of trying to sleep on the cars, said the door slammed against your sore, if that gets no better, won’t you speak to the Dr about it? ↩

-

This is part of “The works of the right honorable Lord Byron”. ↩

-

Private Isaac V. Warner, from Hamden. Isaac was discharged on November 8th, 1862, for “disability”. ↩

-

Early in the war many bold entrepreneurs set forth to make a quick profit off of fear. There were many tools that they sold to preserve the life of the soldier, very few of which had any affect on ones chance of surviving the war. The “armor vest” of which he speaks was one of the more popular of these and were aggressively peddled. In the words of John W. Storrs in his regimental history of the 20th Connecticut Volunteers:

One of the most ludicrous of the articles of merchandise dispensed to the departing soldier was something even less useful, if possible, for the protection of life than were the patent medicines, in the shape of a set of steel plates to be worn inside the waistcoat, and which was numerously purchased by “the boys” with the expectation of wearing them in battle, but which would have made a rebel minnie laugh at the idea of being stopped by so flimsy an obstacle. As far as Washington, these wonderful life-protectors were transported, as baggage, with the public or government property. Thenceforward, however, to become, upon the march, a part of the individual burden, one or two pulls at which sufficed to leave the steel plates (designed to be worn under, the vest) abandoned along the road, or at the first camping ground. ↩